August is Women in Translation-month! Started by Meytal Radzinski in 2014, this annual celebration of women writers from around the world has become a staple of the online literary community – and an event we, as a translation-focused project, want to participate in.

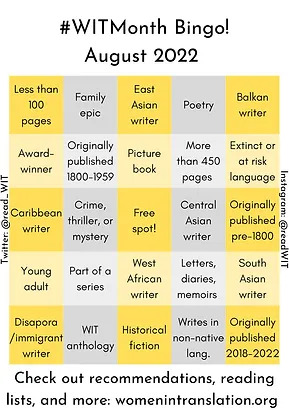

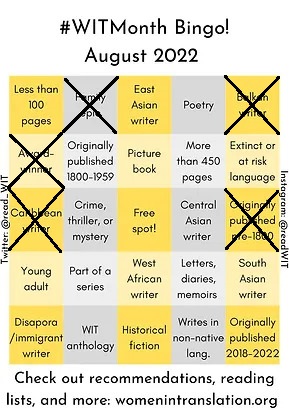

After visiting the official WIT Month website, we couldn’t help but be charmed by last years’ Bingo sheet – so we decided to have fun with it and figure out which of the Bingo squares we could cross off by using the periodicals in our corpus. The following list is based on our current datasets, which consist of translations into English, French, and German (hence the presence of Anglophone authors in our selection). These datasets are not finalised yet, so some categories might get ticked off later on. Although the categories “more than 450 pages”, “WIT Anthology”, “Originally published in 2018-2022” cannot be applied to our corpus.

Here are the first five Bingo squares that we can cross off:

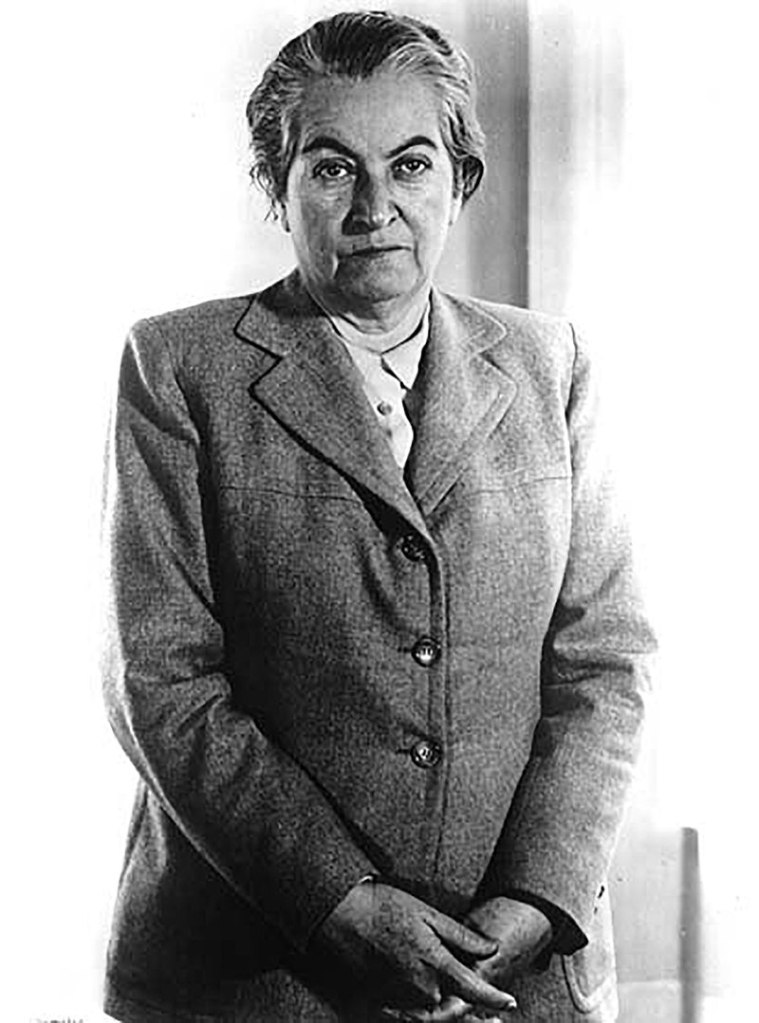

Award-winner: Many of the women writers translated in our magazines were highly renowned and received awards in their respective fields. One example of this is Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1945, just after the end of the war. German magazine Neue Auslese featured one of her poems, “¡Echa la simiente!” [“Sow the seed”], in 1946. The ending of the poem (“Hombre que echas grano, hombre creador, /¡prospere tu rubia simiente!” [“Sowing man, creative man,/ may your fair seed prosper!”]) illustrates Mistral’s use of simple imagery related to nature and humble peasant life, but also the generalised hopes for renaissance and regeneration in the immediate aftermath of WWII.

Other Nobel laureates represented in our corpus include Swedish writer Selma Lagerlöf (the first woman to win the Nobel prize for literature in 1909) and Pearl S. Buck (the first American woman to do so), who grew up and spent part of her life in China, where her parents were Presbyterian missionaries. She then returned to the United States and became an advocate for racial equality, writing extensively about Asia. One such article of hers is featured in Neue Auslese, highlighting how some of our magazines harness the authors’ competence as intercultural mediators in order to broaden their horizons and foster mutual understanding between cultures.

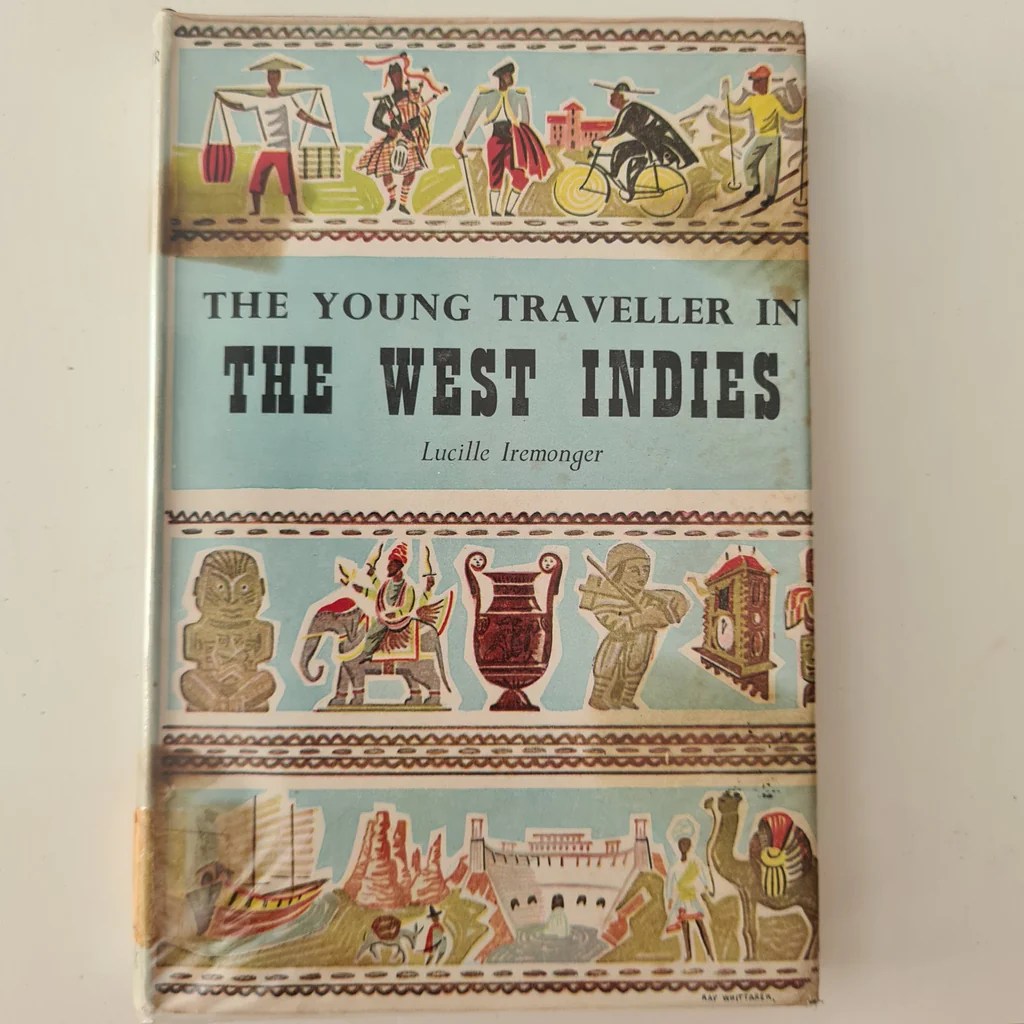

Carribean writer: Born and raised in Jamaica, Lucille d’Oyen Iremonger also lived in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands and in Fiji, before moving to England. She featured various of these locations in her writing. She is, to date, the only Caribbean woman writer translated in our magazines, which speaks to our corpus’s relative lack of diversity, especially when it comes to women writers.

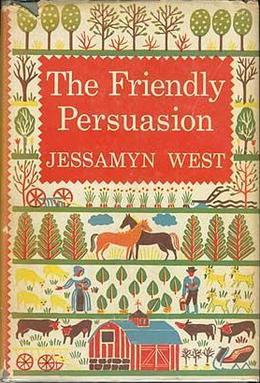

Family Epic: American author Jessamyn West wrote a series of vignettes published first in US literary periodicals and then in book format under the title The Friendly Persuasion (1945). Set in the second half of the 19th century, they tell the story of a Quaker family from Indiana, the Birdwells, loosely based on West’s own forebears (who, incidentally, are also Richard Nixon’s). West later wrote Except For Me and Thee to complete the Birdwells’ family story. The piece translated by Eleonore Nérac-Schoenberner for Neue Auslese (“Lead her like a pigeon”) is part of the original collection and focuses on the character of Mattie (the Bridwells’ eldest daughter) and her approaching coming of age. Its title comes from the folk song featured in the story, “Weevily Wheat”:

Take her by the lily white hand,

Lead her like a pigeon,

Make her dance the weevily wheat

And scatter her religion.

This may seem surprising in the context a publication that was overtly edited by the Publishing Operations Branch of the Anglo-American Information Control Division, and was therefore a vehicle for Allied propaganda in post-war Germany, but the rural setting and everyday themes offer a descentered view of the United States–perhaps one that was more susceptible to cut through the Anti-Americanism of the post-war years. The same is found in the translations of stories by Eudora Welty, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Ruth Suckow, and Willa Cather, conforming a clear line in Neue Auslese. Funnily enough, it is this bingo entry that has brought this trend to light, revealing an unexpected aspect of the intertwinement of literature and public policy in the context of the Cultural Cold War.

Balkan writer: Romanian intellectual Monica Lovinescu claimed asylum in France, where she was pursuing her studies, in 1948. From her Parisian base, she focused her activity on denouncing the newly-established Communist regime in her home country, becoming a central figure of the opposition in exile. Committed to fighting for democracy beyond the Iron Curtain and building bridges between European countries, Lovinescu contributed to numerous cultural magazines, such as those published by the Romanian diaspora (e.g. Luceafărul) as well as Anglophone and Francophone venues linked to the Cultural Cold War. French magazine Preuves, which was published by the Congress for Cultural Freedom (a CIA front organisation aimed at advancing the cause of anti-Communism among European intellectuals), is a good example. She pursued the same objectives through radio programmes, ultimately joining Radio Free Europe in the 1960s.

While most of her oeuvre was written in Romanian, Lovinescu was proficient in French and even translated a number of Romanian works of literature into French. Whether her article published in Preuves was actually a (self-)translation or a piece that she wrote in French, Lovinescu is one of the many fascinating voices of the cosmopolitan, multilingual diaspora that sought to re-imagine Europe in the aftermath of WWII.

Originally published pre-1800: Perhaps owing to the intensity of post-WWII cultural debates, as well as the urgency of re-articulating literary life, a significant portion of the material translated in our magazines is contemporary (or at least from the 20th century). In this context, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, featured in Encounter in Robert Graves’s translation, is a notable exception. In “Arguye de inconsecuentes el gusto y la censura de los hombres que en las mujeres acusan lo que causan” [translated as “Against the inconsequence of men’s desires an their censure of women for faults which they themselves have caused”], the Mexican Golden Age writer, nun, and polymath denounces the contradictory, and ultimately misogynistic expectations surrounding women’s sexuality and love life:

Opinión, ninguna gana;

pues la que más se recata,

si no os admite, es ingrata,

y si os admite, es liviana.

[“However discrete a woman is / she never wins your esteem. / If she doesn’t let you in, she’s mean; / she let you in, she’s easy.” in Electa Arenal and Amanda Powell’s translation].

To what extent Graves’s translation and introductory essay (originally part of his Clark Lectures given at Cambridge in 1954) do justice to Sor Juana’s sharp wit and outspoken social critique is debatable, but her inclusion in an otherwise rather male-dominated magazine is a breath of fresh air. Read more about the translation of Sor Juana’s poem here.

So far, our Bingo sheet looks like this:

What started off as a fun research prompt quickly made us realise the extent to which women writers are under-represented in our corpus, especially in the Bingo’s more challenging categories. While we were surprised to come across many female translators during our work on the project, finding female authors that fit all of the WIT-categories turned out to be much harder than we had anticipated.

Look out for Part Two!

Marina Popea and Dana Steglich

One thought on “Women in Translation (Part 1)”