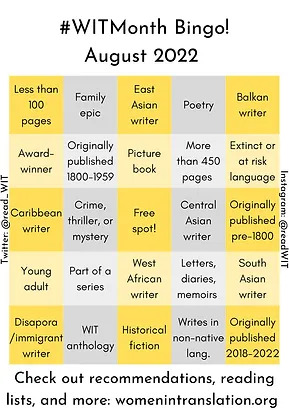

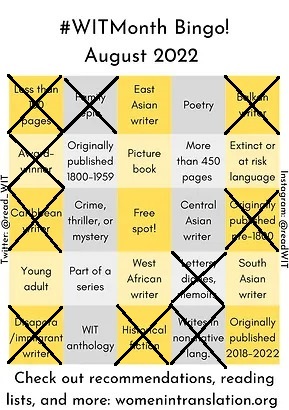

September and October have passed us by but we are still finding more ‘Women in Translation’ in our corpus, so we are continuing our series and checking off more Bingo squares:

Less than 100 pages: This square might be a challenge if you’re trying to find a short fiction writer in a sea of novelists but for a research group focused on periodicals, this is the easiest category to get: every single text in our corpus is less than 100 pages long! Still, we figured we should choose one text and highlight its author (and translator):

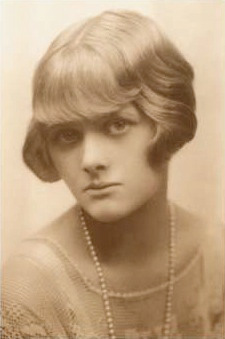

Daphne du Maurier is probably best known today as the author of such classics of suspense as Rebecca (1938), My Cousin Rachel (1951) or Jamaica Inn (1936) and short stories like The Birds (1952). But even though du Maurier’s works became almost instant bestsellers in the early 20th century and many of her stories were adapted into movies, critics didn’t take her writing seriously for a long time.

Like her more famous novels, many of her works were inspired by du Maurier’s surroundings, others were written about people she personally knew or even non-fiction biographies about her family members. Her autobiographical family history The Du Mauriers (1937) follows the family’s move from France to England in the 19th century. The book is part of our corpus because it was published in La NEF in four instalments in 1948 and translated into French by (previously featured translator) Denise van Moppes.

Letters, diaries, memoirs: Du Maurier’s family history is far from being the only autobiographical text in our database. In fact, quite a few of the entries published in our post-war magazines belong to the category of ‘life-writing’. One example we could highlight here is Monica Dickens’ reflection on her great-grandfather – yes, the Dickens – originally published in English in Life magazine but translated into German by one of the many anonymous translators working for Neue Auslese in 1949.

Monica Dickens was a famous writer and fascinating person in her own right, working in many different careers, campaigning for various causes and writing both books for children and adults. She was also a bit of a rebel, even in her early years: Dickens was expelled from school and worked as a cook and a domestic servant despite – or in order to spite? – her privileged upbringing. Her experiences as a servant and later on as a combat nurse as well as her work in an aircraft factory informed her writing in several books: One Pair of Hands (1939), One Pair of Feet (1942), My Turn to Make the Tea (1951). Today, she is probably most famous for her Follyfoot-series, tales of horses and farming communities for children.

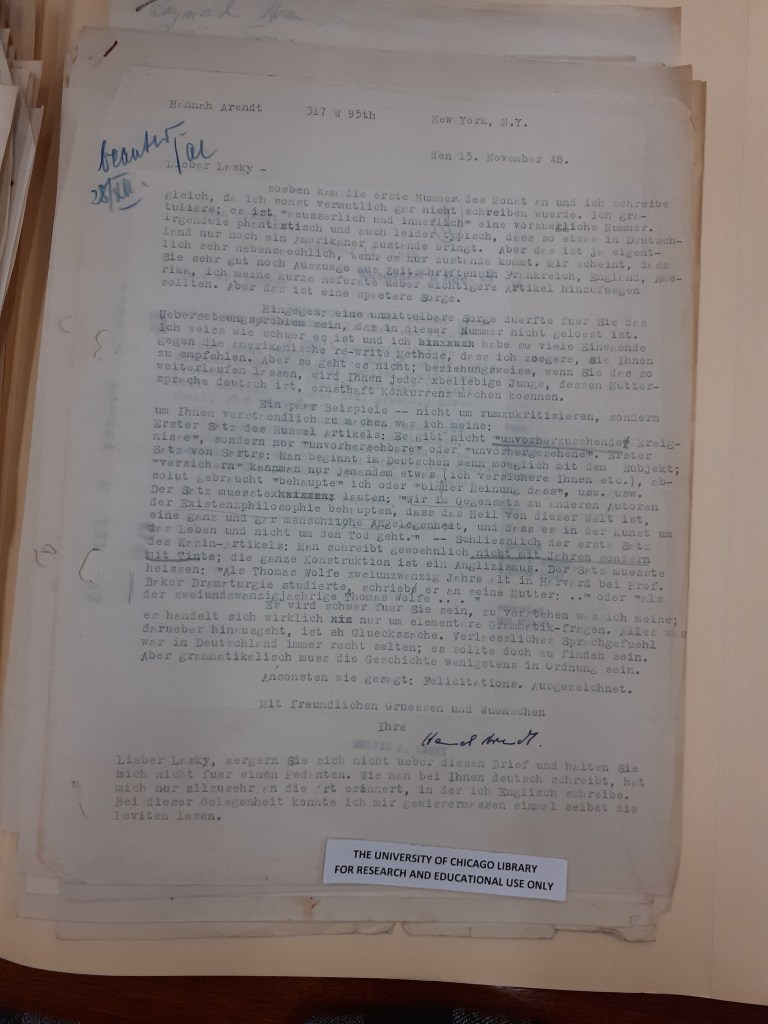

Diaspora/ immigrant writer: Again, many of the writers in our post-war corpus were immigrants. Many not only immigrated to a different country but a different continent (i.e. North America) altogether. One of the most famous American immigrants published in multiple magazines in our corpus is German philosopher Hannah Arendt. Her English-written works were translated (and self-translated) into French and German. Arendt herself needs no introduction; which is why, instead of writing one, I will focus on the importance placed on Arendt’s good opinion by the editors of German magazine Der Monat.

Without any of her own material being published in it, Arendt wrote a lengthy critique of the translation done in the very first issue of Der Monat: “An immediate concern for you,” she told co-editor-in-chief Melvin Lasky, “should be the translation problem, which is not solved in this issue. […] it doesn’t work this way; or rather, if you let it go on like this, any boy whose native language is German will be able to give you serious competition.”

She then goes on to list specific translation errors in her letter. This letter by Arendt was taken to heart by the editors, every single complaint voiced by Arendt was answered in great detail by co-editor-in-chief Hellmut Jaesrich, and in her answer to Jaesrich, Arendt suggests that it might help Der Monat if they were to publish the translators names along with their work because it would make them feel “responsible” for it.

Historical fiction: Finding texts from specific fiction genres turned out to be a much tougher task than any of the previously discussed prompts. ‘Historical fiction’ especially is a category we thought we might need to give up on because the genre hardly lends itself to publication in a periodical. But while scanning through our database to find something that could qualify, we came across a translation of The Edwardians (1930) by Vita Sackville-West.

The novel is one of Sackville-West’s later works and – continuing a theme of this blog post – inspired by her own childhood. It offers a critique of aristocracy, gendered double standards and social conventions. Since the plot mainly takes place between 1905 and 1910, we feel that we’re allowed to call this Bildungsroman historical fiction and claim the Bingo square.

Writes in non-native language: A surprising number of the authors we considered for this final category wrote in French but were born in Eastern European countries where French is most certainly not the national language – although it might have been this authors’ (and many others) first language:

Romanian-born Marthe Bibesco (1886-1973) was fluent in French, the language of the educated class, at an early age – allegedly even before she spoke Romanian. Subsequently, she also published in French. Like almost all of our featured authors on this post, Bibesco was born into and socialised with the aristocracy. As part of the cosmopolitan elite, Bibesco was friends with many European intellectuals such as Paul Valéry, Rainer Maria Rilke, Winston Churchill and even Vita Sackville-West.

In 1908, Bibesco became an instant success with her first memoir Les Huit Paradis and she went on to write numerous critically acclaimed novels as well as popular romances under a pseudonym.

As you can see, we’re getting close to our first “bingo” … Check back in for Part III and find out where it happens!

Dana Steglich