The important role played by women editors of Anglophone modernist little magazines in the early twentieth century has long been acknowledged. Whether it is Harriet Monroe founding Poetry: A Magazine of Verse (1912), helped by Alice Corbin Henderson, or Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap starting The Little Review (1914), Dora Marsden and The Freewoman/ New Freewoman/ Egoist, or writers such as H.D., Katherine Mansfield, or Marianne Moore, all of whom acted as editors of magazines, the first half of the twentieth century has many stories of how women contributed in significant ways to the development of modern magazine culture.1

One might expect that after 1945 this trend would continue and perhaps increase in the corpus of magazines we are studying at SpaTrEM, as the post-war consensus in Western Europe led to increased opportunities for women in employment and education. Our project has, for example, identified a large number of women who acted as translators in the magazines we are studying. However, in terms of editorial roles for women it is noticeable that the picture appears much sketchier.

There are no named editors of any British magazines in our corpus but there is evidence of women playing some kind of editorial role in a number of them, although the extent of their contributions is hard to ascertain. At The London Magazine, edited by John Lehmann, there was an editorial advisory board of five, with Elizabeth Bowen being the single woman. However, Barbara Cooper was listed as one of two Editorial Assistants and had acted as Lehmann’s secretary since 1939, when he was editor of New Writing. Lehmann in his autobiography indicated that Cooper did play a significant role in the work of the magazines, displaying the ‘three qualities which from the point of view of a literary editor were almost – in combination – too good to be true: a near-fanatical loyalty, an infallible memory and unquenchable zest for reading manuscripts, no matter how dreary, pompous, silly, ill-written or ill-typed.’2

In the case of the German magazines in our corpus there is only a little more evidence of women carrying out editorial duties. One of the founders of Karussell was Berlin-born, Maria-Harriet Schleber, who also ran a publishing house in Kassel, and married Georg Aldor, a cultural official with the American occupying forces who also helped found the magazine. It is said that Schleber also helped develop a literary and cultural network in Kassel in the post-war years. Margaret Greig was also a co-founder and editor of the short-lived bi-lingual (English/German) magazine, The Gate/ Das Tor, but little information can be found about her.

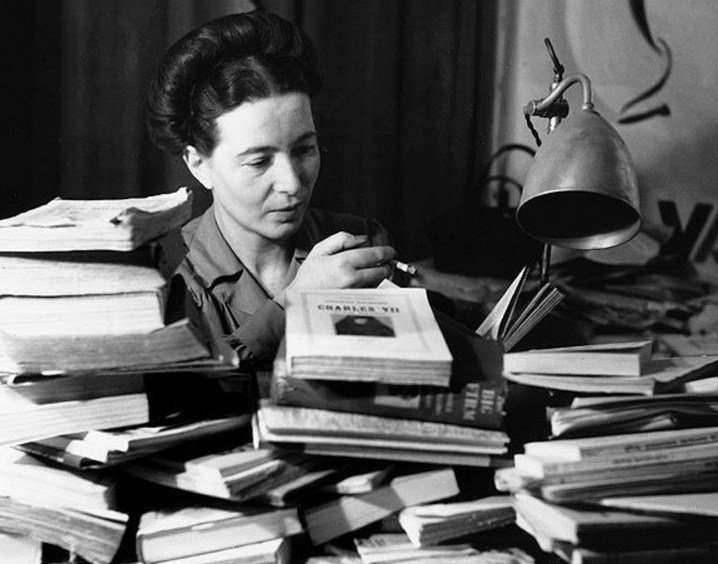

However, in the case of the French magazines in our corpus we have two significant examples of women in editorial roles. Although Jean-Paul Sartre was listed as the ‘Directeur’ of Les Temps Modernes, it is clear that Simone de Beauvoir also played an important role in the editorial work of the magazine. She was on the initial editorial board but was also involved in other aspects of the production such as overseeing the layout of the magazine. Significantly, De Beauvoir was in charge of the literary output of Les Temps Modernes, reading the submitted manuscripts and becoming, according to Stève Bessac-Vaure, a ‘cultural mediator’ for foreign literature in the magazine.3 This is, of course, in addition to her own contributions to the magazine, such as extracts from The Second Sex or her diary from the United States (‘L’Amérique au jour le jour’).

Less well-known than De Beauvoir, but equally important in post-war French periodical history, is Lucie Faure (1908-77).

Faure, along with Robert Aron, was the founding editor of La NEF (Nouvelle Équipe Française). Along with her husband, Edgar Faure (later the Prime Minister of France), Lucie Faure escaped to Algeria during the war, and was attached to the Foreign Affairs Commissariat of the Committee of National Liberation. La NEF began publishing in Algeria in 1944 before returning to Paris as, reputedly, the first magazine to appear there after the end of the war. Faure remained as editor until her death in 1977, becoming sole editor in the mid-1950s and overhauling the look and contents of the magazine several times during her tenure. Initially the magazine tended to focus on literary matters (with special issues on Soviet Literature and Surrealism) and published many works in translation (including Elizabeth Bowen, Daphne du Maurier, and Richard Wright). La NEF shifted in the 1950s to focus more upon contemporary political and cultural affairs, with special issues on such topics as the radio, television, medicine, the police, the Algerian war, and racism. The final issue of 1960 and the first issue of 1961 was devoted to the topic, ‘La française aujourd’hui’. Faure opened the two themed issues by writing on the contemporary situation facing women in France, and the inquiry concluded in the 1961 issue with an essay by De Beauvoir on ‘La condition féminine’.

Just as the work of translation is often said to be invisible, so also is the hidden hand of the editor and a figure like Faure deserves more attention by historians of periodical studies.

Andrew Thacker

1 Jayne E. Marek’s Women Editing Modernism: “Little” Magazines and Literary History (1995) was one of the earliest works to analyse this phenomenon.

2 John Lehmann, I Am My Brother (London: Longmans, 1960), p.144.

3 Stève Bessac-Vaure, Simone de Beauvoir – A Humanist Thinker (Brill, 2015), p.58.